|

By Sarah Schumann In the fisheries world, we tend to talk about the party and charter boat fleet as if they were two halves of the same coin. After all, both sectors are in the business of providing bait, helpful tips, and a moving platform at sea to help recreational anglers maximize their catch and enjoyment. And for the most part, the only aspect in which they truly differ is in their size. In a pandemic-stricken world, however, size matters – and being small, it seems, offered a distinct advantage for charter boats in 2020. According to rumor, six-pack charter boats (so-called because they are licensed to carry up to six passengers) may have had one of their best seasons in recent memory, while their neighbors in the party boat fleet had a dismal year. To learn more, I talked to Mike O’Grady, who has an insider’s view into both sectors in Point Judith. O’Grady is a longtime captain on the Frances Fleet party boats, and more recently launched a charter business on his 38-foot vessel, Fishing Machine. The spring season was rough for both party and charter boats, O’Grady explains. The complete shutdown that occurred during the first few months of the pandemic forced all for-hire boats to cancel reservations and miss out on squid season. That was bad, but it could have been worse, O’Grady says: if a shutdown had to happen, the early spring shoulder season was probably the best time for it. Phase II of Rhode Island’s reopening allowed for-hire vessels to begin operating again at reduced capacities in June. This was when the fates of party and charter boats began to diverge. “Party boats got hit the worst because their carrying capacity got hit,” O’Grady explains. This is because party boats charge by the head, so any reduction in their capacity can have large implications in terms of revenue. Reopening guidelines used a formula that factored in a for-hire vessel’s length and beam to calculate the number of anglers who could safely fish together on a trip. For the Frances Fleet, this meant carrying a maximum of 27 people per trip on a boat designed to hold 136. Although this number rose to 40 over the summer and to 89 by fall, the business had to run for a full season on a partial customer base, earning only partial revenues. One unexpected silver lining of these capacity reductions, O’Grady observes, was that they unleashed a sort of demand-smoothing effect. Usually, customer demand peaks on weekends and softens on weekdays, he explains. “But one of the weird things that happened out of this is that people were looking to book those days that would be a little bit lighter. You didn’t really have your low, low days. Bookings were at a premium and people didn’t want to get shut out.” Like party boats, charter boats also had to reduce their capacity to meet social distancing rules. But since charter customers pay by the trip rather than the head, capacity reductions had a smaller effect on revenues. More importantly, many customers seemed to feel that charter boats were a lower-risk environment than party boats, O’Grady observes. For example, on charter boats, customers could book trips with other members of their Covid pods. “Some people gravitated away from the party boats to go on the six-pack because it’s a little more of a controlled atmosphere,” he explains. “You book a trip with six people you’re comfortable with. Some people were reluctant to get on a party boat with a bunch of strangers.” “As the summer went on,” O’Grady recalls, “demand was really good.” In fact, he feels that the pandemic “generated a small uptick in new business” for charter boats. Although both party and charter boats suffered from a downturn in out-of-state visitors, and captains missed seeing some of their long-time customers in at-risk age groups, they saw an increase in first-time anglers looking for a new hobby while their usual summertime leisure activities were off-limits. “I was adding on some afternoon trips,” O’Grady says. “A lot of the charter boats were getting calls to do afternoon trips. There was definitely a drive of first-time people.” “Hopefully people who were exposed will generate some return business going forward,” O’Grady muses, adding that the industry has long suffered from a graying trend among its customer base. If new people got hooked on angling as a result of the pandemic, it would be a blessing in disguise. “I hope people get introduced to it,” O’Grady says. “I think that’s one of the things that seriously affecting our industry, aside from Covid. People don’t do things to get their hands dirty. Kids nowadays are raised with the tablets and screen. To get them to go outside on a colder than normal day? They’re so used to the air conditioned or heated environment. To go out and do hunting or fishing or something that requires some patience and some inner fortitude and some persevering through some weather or rain? The biggest issue that our industry is battling is trying to get people to do things that involve getting dirty.” Only time will tell if this new trend has staying power. In the meantime, O’Grady and his fellow for-hire fishermen are focused on trying to get through the immediate twists and turns of the pandemic.

Each new phase and season seems to present its own challenges. For instance, the Frances Fleet offers cod trips all winter long, but the lower temperatures make it harder to maintain social distancing, as customers want to spend more time in the heated cabin and less time out on the rail while vessels are underway. “You definitely notice as the country has had that uptick in the last month or so, people cancelling trips because they couldn’t travel or because they’d have to quarantine when they get back. Over the winter, I think we’ll see a drop-off in customers.” Party and charter boat fishermen: Would you benefit from technical assistance or marketing advice to help your business recover from the pandemic and keep new anglers engaged in fishing? Team up with the Fish Forward project! About Fish Forward: From now until September 2021, the Commercial Fisheries Center of RI and RI Small Business Development Center are teaming up to support business innovation and resilience in the seafood sector, thanks to general funding provided by the federal CARES Act. Contact [email protected] for more information or to get involved.

3 Comments

By Sarah Schumann F/V Briana James Sometimes, even the best laid plans go astray. Just ask Point Judith fisherman Jim Leonard. Though only thirty-four, Leonard already has twenty-five years of fishing under his belt. But it wasn’t until late last year—after crewing for family members, diving for quahogs in Narragansett Bay, and fishing up and down the Eastern seaboard as a deckhand with the offshore Seafreeze fleet—that he achieved his career goal of becoming the owner and captain of his own inshore dragger, the F/V Briana James. That pivotal moment was long in the making. Leonard purchased the vessel that would become the Briana James in 2016. Over three winters, he rebuilt her from the waterline up—laying a new deck, opening the transom to make way for a stern ramp, reengineering the hydraulic system, and rigging her up to become an inshore dragger. Named for Leonard’s wife and infant son, the Briana James arrived in her new homeport of Point Judith in August 2019. But in Leonard’s plans, 2020 was going to be the year when she really began to shine. It would also be the year when she would finally begin to earn her own keep. Unfortunately, 2020 had other plans. “All of a sudden, I start fishing, and then we start hearing about this ‘pandemic’ or this ‘virus,’ Leonard recalls. “I remember coming in one day. I had a really nice trip on. I had a couple thousand dollars in fish. But I had to throw it overboard, because [the dealers] were closed. I don’t understand. I just poured every single thing I had into this boat. What do you mean, you’re not taking my fish?” With prices for some species slashed by seventy-five percent compared to a typical year, Leonard was staring at credit card bills from the boat-building work, with no easy way to pay them off. “As I sit right now, with the brand-new boat and license, I’m into my vessel right now like two hundred and seventy thousand dollars,” he estimates. “We went overboard on a lot of things. But I went overboard on a lot of things because I was expecting big outcomes.” “All the while building the boat,” he adds, “we had all this hope. Prices were through the roof. Guys were making awesome money.” But many of the species that Leonard catches—fluke, squid, black sea bass—are highly dependent on the restaurant market. With restaurant sales curtailed for much of 2020 as a result of social distancing measures, demand for these species remained depressed throughout the year. Leonard’s status as a first-year boat owner has made him particularly vulnerable. When Congress set aside relief funds in the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, it designated these funds for fishing businesses with a revenue loss of at least thirty-five percent as a result of the pandemic, compared to their preceding five-year average. After spending the last three years investing in a boat that was finally expected to start to generate revenues in 2020, Leonard found himself out of luck. When the Department of Environmental Management (DEM) announced in April that they would temporarily offer fishermen the ability to sell seafood directly to the public from their vessels through a new Direct Sales Dealer License, Leonard and his wife Briana Martin jumped at the chance to participate. “To be quite honest with you, it was a no-brainer,” Leonard explains. “It was the only option we had.” Selling directly to customers in Point Judith The couple began selling fish every Saturday, next to their dock in Point Judith. They set up a website. They got active on social media. They pitched their story to local television stations. They posted their catch to Fishline, a new smartphone app that that connects local customers with fishermen selling seafood direct. “Having that option to do the dockside sales was awesome,” Leonard reflects. “I went at that thing with my head and my horns down.” At first, Leonard and Martin’s efforts paid off. Lines of customers snaked around the parking lot. Fish sold out in no time. “The beginning was the best, when everybody was panicking,” Leonard observes. “When we started selling fish, it was literally like we were having a zombie apocalypse. I’ve seen people with suits and ties on who were spending hundreds of dollars. ‘Oh, I’ll take that!’ You hold up the biggest fluke, and within five minutes, it was gone. We were selling out fluke for ten bucks a pound.” But as the summer wore on and the public’s sense of alarm wore off, demand for direct seafood sales began to wane. “It worked for a little while,” Leonard says. “But then when everybody settled down and toilet paper came back to Walmart, it kind of went to where it was almost not worth it.” After twenty-five dockside sales events, Leonard and Martin called it quits. Several factors weighed into this decision: the weather (which makes fishing days unpredictable, especially in the autumn months), the availability of babysitters (they have two kids, ages one and three), and a regulatory condition stipulating that Direct Sales Dealer licensees may not retain their catch for longer than twenty-four hours after landing it. Though intended to protect public health, that requirement was particularly onerous for licensees to meet while remaining profitable. As Leonard explains, “I come in from a half a day of fishing at twelve o’clock, twelve thirty, maybe one, in order to just sell fish to the public for an hour, before I have to say, ‘Ok, that’s it. We’re done. Pack it up. Untie the boat. We’re going to bring the rest of the fish to the coop before they close at three, before [otherwise] I have to throw it over the rail of my boat.” Even so, Leonard says the chief weakness of the direct sales program was not the twenty-four-hour rule, but a lack of publicity. “We stopped because the people stopped coming,” he explains. “I just wish someone could put this on a commercial and explain to them that if you showed up to Point Judith on a Saturday or you went on Facebook or our website or something, or called the phone number on the side of my truck, that you could come get a piece of real, fresh-caught, wild fish from state waters that was caught and landed inside of twenty-four hours. You could take it home to your family and eat it. It’s just something that needs more publicity.” Summarizing his experience with Rhode Island’s first-ever direct dockside sales program for fish, Leonard concludes, “We did ok with it, but it wasn’t a savior.” Now, with Covid cases on the rise and a long winter ahead, this first-year captain is plagued by anxiety. “It’s turning more into like I spent this money to go to jail,” Leonard confesses. “I mean, it’s fun. It’s great. I feel achieved. It was my dream. But now it’s turned into a burden, depending on how long this coronavirus is going to happen. To me, it’s just not worth me going out [fishing]. Sounds like a lot of money, going out and having the boat stock five hundred dollars when you’re by yourself. [But] that five hundred dollars was twenty-five hundred dollars last year.” Fishermen: Are you interested in upping your direct sales game? Is your business struggling as a result of the pandemic? Then contact the Fish Forward project to get free and confidential support from a team of advisors who are here to help you stabilize or even grow your business during these complicated times. About Fish Forward: From now until September 2021, the Commercial Fisheries Center of RI and RI Small Business Development Center are teaming up to support business innovation and resilience in the seafood sector, thanks to general funding provided by the federal CARES Act. Contact [email protected] for more information or to get involved. By Sarah Schumann Chef Kevin DiLibero is the Director of Culinary Arts at the Newport Restaurant Group, an employee-owned company with twelve restaurants around Rhode Island and nearby Massachusetts. Many of the company’s restaurants pride themselves on good seafood, but two—Hemenway’s in Providence and The Mooring in Newport—stand out among the best-known seafood restaurants in the state.

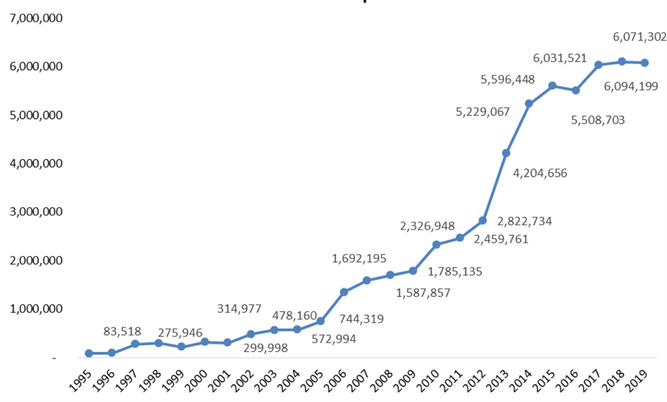

For DiLibero and his restaurant chefs, including Max Peterson at Hemenway’s and Jennifer Backman at The Mooring, the Covid-19 pandemic has brought with it a keen awareness of how the factors that impact restaurants can also impact local farmers and fishermen upstream. At no time was this starker than on March 15, when the company made the difficult decision to close all of its restaurants for a time, in order to keep its employees safe. “With the closure of all our restaurants back in March, there was an understanding that the ripple effect was very large,” DiLibero reflects. “The fishermen still had to fish, but there was nowhere to sell their fish, in the sense of really moving pounds, because all the restaurants had closed. We were going into spring, graduation, Mother’s Day. There were a lot of lost sales on both ends.” As the company’s restaurants gradually reopened—first for take-out only, eventually for in-house service at half-capacity by the end of June—they had to reinvent many aspects of how they did business. Each phase presented its own set of operational challenges and its own implications for the quantity and variety of local seafood the restaurants were able to offer. For instance, DiLibero explains, putting seafood in take-out packages is logistically challenging because many types of cooked seafood don’t travel well. Additionally, customers ordering their take-out online do not benefit from guest-server interaction that takes place through in-person dining. As a result, they are more likely to gravitate towards items they have tried before and know they will like. “There’s really not a lot of human interaction in a sense,” says DiLibero of take-out ordering. “It’s tough to really truly educate someone through takeout.” Even when the group’s restaurants reopened for in-house dining, operating at half capacity meant making some tough decisions about which seafood to offer and which seafood to cut. Before the pandemic, “All of our properties had very large menus. Some of them had fifty-six items,” DiLibero explains. “Now they only have thirty-five. Now our menus don’t offer as many varieties. We just can’t carry that kind of inventory because we don’t have the foot traffic coming through the door. Hemenway’s and The Mooring would have twelve to fifteen different species of fish on their menu. That’s not the case right now.” Relying on analytics such as “menu mix” – a tool that allows food service businesses to calculate the relative percentage of sales that each menu item contributes to the business’ overall profitability—DiLibero and his restaurant chefs opted to go back to basics. For seafood, this meant keeping salmon, swordfish, tuna, littlenecks, scallops, oysters, and lobsters on the menu, while downscaling the variety of local seafood. “When a chef and a kitchen have conviction, they’ll be able to move skate, scup, bluefish, tautog, striped bass,” DiLibero says, noting that Chefs Backman and Peterson made efforts to keep these species in their offerings this summer. However, a pandemic may not be not the best time for restaurants to introduce diners to underappreciated or unfamiliar local species. “We’re not able to keep specialty products on our menus that we don’t know are going to sell.” Nonetheless, the Newport Restaurant Group never wavered in its commitment to purchasing from local farmers and fishermen, DiLibero says. For instance, the group’s restaurants continued to offer fisherman Chris Roebuck’s “Wild Atlantic” sea scallops throughout the season. “That was a decision to keep those scallops on the menu. When you have a connection with an individual, you want to make sure that you protect that relationship. That was important to me, to make sure that those scallops stayed on our menus. These are the things that tie us to these local purveyors that will never leave us. Short term or long term, that’s our focus.” In the short term, DiLibero is feeling enthusiastic about the start of the Nantucket bay scallop season, which kicked off this past Sunday. “I get very excited about that, because it’s probably one of the best seafoods out there. There’s always a focus on highlighting things that are very special to the New England area, and Nantucket bay scallops are one of them.” Looking further down the road, DiLibero is more cautious. “From an operational standpoint,” he explains, “it’s tough when we’re not running our own restaurants right now. The government is. If they tell us that we have to shut down, well, we have to shut down.” “It’s an ever-changing world that we live in,” DiLibero muses. This prompts him to reflect on the things he’s been most grateful for this year. “You realize the good in the people that you have. A lot of people did a lot of things that they didn’t have to do, but they did them because they love this company so much—all pitching in to help each other out to just make things good. That’s been very rewarding…I would say we will come out of this on the other side a better and smarter company for this. There’s always something to learn from hard times.” As for this year’s most distressing aspect, DiLibero says “it’s just knowing how difficult it’s been for the world itself. We have such a good connection with a lot of the local farmers, and how difficult it’s been for them…. Just knowing how tough they’ve had it. And the fishermen. It’s a humbling experience through these times.” Fishermen, seafood businesses, and chefs: Do you want to see more customers ordering Rhode Island seafood in local restaurants? Team up with the Fish Forward project to make your ideas a reality! About Fish Forward: From now until September 2021, the Commercial Fisheries Center of RI and RI Small Business Development Center are teaming up to support business innovation and resilience in the seafood sector, thanks to general funding provided by the federal CARES Act. Contact [email protected] for more information or to get involved. By Sarah Schumann Brawley and assistant Katie Martin with some of this week's harvest. Over the last decade, oyster aquaculture has been one of Rhode Island’s fastest rising industries. But this flourishing sector is unlikely to experience much growth this year, says Graham Brawley, manager of the Ocean State Shellfish Coop. In fact, it may be among the local economic sectors hardest hit by the Covid-19 pandemic. Like most oyster businesses across Southern New England, the Coop sells 100 percent of its product into the raw bar market. “There is no other destination for Southern New England oysters,” Brawley states plainly. Raw bars, with their skilled shuckers, depend in turn on dine-in restaurant traffic. With restaurants closed or operating at reduced capacity this spring and summer to slow the spread of Covid-19, oyster sales were a predictable casualty. Typically, the Ocean State Shellfish Coop varies its business model with the seasons. In summer, when local demand swells due to coastal tourism, it sells most of its oysters to Rhode Island wholesalers who pick up directly from the Coop’s facility on Walt’s Way in Narragansett. In winter, the Coop ships its product to larger wholesalers serving out-of-state metropolitan areas. It was operating in winter mode when the pandemic struck. “It was March 11,” Brawley recalls. “That’s the date that I remember when things just stopped.” After receiving calls from wholesale customers who were suddenly stuck with unsalable inventory, the Coop made the difficult decision to accept returns and offer refunds. “I brought oysters back, so that farmers could put them back on the farms, just to sort of help bail out some of the wholesalers,” Brawley recounts. “They had tens of thousands of oysters in their coolers, and they weren’t going anywhere.” With springtime sales reduced to a trickle, the Coop -- which has six member farms but regularly purchased from up to fifteen farms before the pandemic – also had to decide how to allocate its limited sales opportunities. “I had to scale back a little bit on the number of farms,” Brawley explains. “I had to basically say to guys who’ve been selling through the full year, I’m going to stick with you. But some of these smaller guys, I just can’t put it on my plate or on our list for that matter. Because it wasn’t like people were knocking on our door looking for new oysters.” Thankfully, the partial reopening of restaurants over the summer threw a lifeline to the industry, says Brawley. “June, July, and August were fairly robust. There was plenty of demand for that local flavor and taste for the oyster, which was great.” But even so, the Coop’s sales never exceeded 60 percent of their typical summer volume. What troubles Brawley the most is thinking about this coming winter. Although he expects a small uptick in sales during the holiday season, his outlook is generally bleak. “In the winter, when the local market takes a significant dip, I can always count on New York and Boston,” he explains. “And I think that we haven’t seen the worst of it for New York and Boston.” Accordingly, many oyster growers planted fewer seed oysters than they would normally plant for next year’s harvest, Brawley says. Many have postponed boat and equipment purchases or put business expansion plans on hold. Federal relief programs like the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act) have helped hold the oyster industry together at the seams. Many growers took advantage of the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP), enabling them to pay their crew to tend oysters and maintain gear even after as sales figures plummeted. Brawley and his assistant Katie Martin received Pandemic Unemployment Insurance (PUA) while furloughed this spring. The CARES Act also helped alleviate one of the most vexing aspects of the pandemic for oyster growers: the fact that even though sales were on hold, nature was not. The summer surge in phytoplankton production provided extra nutrition for unsold oysters, and by August, oversized oysters taking up so much farm space that there was little room for next year’s crop. To make matters worse, these oysters had outgrown the raw bar market: their colossal size made them tough to shuck and awkward for customers to slurp down in a single dainty sip. The CARES Act helped by compensating Rhode Island growers to plant their oversized oysters in areas with degraded water quality, in hopes of restoring wild reefs to support enhanced water filtration and fish habitat. This was a temporary expansion of the US Department of Agriculture’s Environmental Quality Incentive Program (EQIP) program, which works with oyster growers to seed spat-on-shell oysters on restoration reefs. The nineteen oyster growers who participated in the program received a combined total of $809,000 for their oversized oysters this summer. This ups and downs of 2020 have forced Brawley and others in the Rhode Island oyster industry to focus on the importance of diversification as a strategy to buffer against future shocks. Brawley has a few suggestions to offer. “I think that there’s an opportunity for small businesses to set up a commissary kitchen on this side [of the state], to give guys that may have ideas for value-adding their product an opportunity to do that,” he says. A commissary kitchen is a shared kitchen space like the Warren-based Hope and Main facility. There is currently no equivalent facility in South County. But Brawley’s long-term vision for Rhode Island oysters goes even further, to what he calls “the big picture.” “Our market is strictly part of food service, food industry,” Brawley states. But what if we thought of oysters as more than food? Building on the thinking behind the EQIP program, he suggests exploring additional markets for oysters that are based around the ecological services they provide: not just water filtration, but also protection from the harmful effects of climate change. “Turning oyster crops from strictly a niche food item into a tool for environmental resilience long term is essential,” Brawley asserts. “Covid is here right now, but the changing shoreline is here for the next twenty-five years. What truly is this industry’s legacy? Is it just for a raw bar industry that clearly can be shut down pretty fast with a pandemic? Or does it become more of a solution? We should be thinking about building up our shoreline with some reefs that help in case storms come along. That would be huge. But that would take a different mindset that what exists right now.” In 2019, the 81 farms comprising the Rhode Island aquaculture industry tallied $5.74 million in sales [1]. This year’s figures will no doubt be quite different. But in Brawley’s view, if the crisis of 2020 can foster a more imaginative vision of what an oyster-based economy can look like, then perhaps it will have at least one silver lining for Rhode Island’s young aquaculture industry. Total dollar value of aquaculture in Rhode Island, 1995-2019. [1] [1] These figures include oysters, other shellfish, and seaweed. Oysters are Rhode Island’s main aquaculture crop. Source: Beutel, D. 2019. “Aquaculture in Rhode Island 2019.” Coastal Resources Management Council. http://www.crmc.ri.gov/aquaculture/aquareport19.pdf.

Fishermen and seafood businesses: What is your imaginative vision for your business or industry? Team up with the Fish Forward project to make your ideas a reality! About Fish Forward: From now until September 2021, the Commercial Fisheries Center of RI and RI Small Business Development Center are teaming up to support business innovation and resilience in the seafood sector, thanks to general funding provided by the federal CARES Act. Contact [email protected] for more information or to get involved. By Sarah Schumann What should a business do when 80 percent of its customer demand dries up overnight? That is the question that Tom Lafazia and his coworkers were faced with in March 2020. Lafazia is the Purchasing and Sales Manager at Narragansett Bay Lobsters, a small seafood wholesale business that has served the Point Judith dayboat fleet since 1996. Eighty percent is the portion of its seafood that the company delivers to restaurants in Rhode Island, Southeastern Massachusetts, and Eastern Connecticut in a typical year. But this was no typical year. In March, as fears of a coronavirus pandemic spread across the world, restaurants across Southern New England closed their doors – some to protect the health of their staff, some to stave off economic loss, and some to comply with state government mandates that ordered a stop to in-house dining for several months in spring 2020. Wholesalers like Narragansett Bay Lobsters didn’t have much time to make a plan. Inshore boats, just gearing up for the season, were demanding to know whether there would be a market for their catch. Lafazia had to do something, quickly. “We pretty much started banging the phones,” he recounts. “We reached out to a lot of retails. We started doing more with Dave’s Market and smaller mom-and-pop retails. We got really aggressive. It was either that or shut down.” By working the phones overtime, Lafazia and his team were able to increase the company’s sales to fish markets and supermarkets by about 30%, helping to make up for some of the lost restaurant revenue. But what really saved the season was the introduction of a totally new sales channel into the company’s portfolio: home delivery. “I don’t think we could have kept going on a seven-day schedule without incorporating that into what we were doing,” Lafazia declares. Setting up a home delivery program was “a learning curve, for sure,” he admits. In addition to reconfiguring their fleet of refrigerated trucks and staff of eighteen to package and deliver small orders, Lafazia and his team had to figure out how to promote the new home delivery program. Having focused almost exclusively on wholesale efforts in the past, they were inexperienced at advertising their products to home consumers. “We talked to a lot of friends and stuff like that, had them putting the word out and getting involved in the social media,” Lafazia recalls. “I did some news and radio interviews.” Orders started flooding in, and with the orders came a lot of questions. “We’ve had people ask if they can keep their lobsters in the bathtub overnight. Or they’re buying raw shrimp and trying to eat them without cooking them,” Lafazia says. “Some people have no clue. It’s like, ‘No, you can’t keep your lobsters in the bathtub overnight. They will die.’ It’s been a ton of off-the-wall questions like that.” Some of these inquiries helped Lafazia realize that he, too, could benefit from improving his seafood cooking skills. “I can cook some fish, but I’m certainly no chef,” he admits. “It’s sort of fly-by-night when I cook something. A little salt, a little butter. I’ve been trying to bump that up a little bit – my knowledge and stuff like that.” In fact, this new emphasis on learning is one of the most valuable aspects of the home delivery program, Lafazia observes. “It introduces people to a lot of the things that they wouldn’t typically buy. It gives people a little bit more of a realization of what fresh seafood actually can be, versus a lot of what you see in the supermarkets. People rave about it.” Although home delivery was a spur-of-the-moment response to a specific shock, it is here to stay at Narragansett Bay Lobsters, says Lafazia. In fact, the company will soon launch a new website with recipes and tips to help consumers prepare more seafood at home. It also plans to expand the program beyond the fifteen Rhode Island cities and towns that it currently serves to include all of Rhode Island and Eastern Connecticut. This doesn’t mean that that Lafazia is sanguine about the future. Although sales to restaurants were surprisingly strong during the peak of the summer thanks to restaurants’ resourcefulness around outdoor dining, Lafazia is concerned that “as it gets colder, they’re not going to be able to accommodate the volume that they need.” If in-house dining is shut down again as it was in the spring, he predicts that beverage sales will plummet, depriving restaurants of a significant portion of their profits. “A restaurant can’t operate on 25 or even 50 percent,” he says. “The winter is definitely going to be tough.” In addition to diversifying its customer base, Narragansett Bay Lobsters is making efforts to diversify its purchasing base. For example, it has been offloading catch from four out-of-state longline boats for the last two summers. Hailing from New York, South Carolina, and Florida, these boats bring in up to twenty thousand pounds of tuna or swordfish each trip. Before Lafazia began courting these boats, they delivered their catch to New Bedford and other ports in the region. Their entry into the Point Judith community has been a boon, Lafazia says. “Dan [Costa] at DEM has been accommodating with helping me get these guys berthing and landing permits. We’re getting ice through other guys. The fuel guy’s getting stuff done with them. It’s really been a broad spider web. Champlin’s, George’s – they all go over there and drink and stuff, so they’re getting some action. It’s been good. Plus, some killer fish have been coming into the port.” Looking ahead, Narragansett Bay Lobsters intends to continue riding what Lafazia describes as a wave of demand for local seafood. “It’s always been our theme anyway,” he says. “That’s it. It’s no big science. We’re just taking it was it comes. No one really knows what to expect. I certainly don’t.”

Fishermen and seafood businesses:

Team up with the Fish Forward project to make your vision a reality! About Fish Forward: From now until September 2021, the Commercial Fisheries Center of RI and RI Small Business Development Center are teaming up to support business innovation and resilience in the seafood sector, thanks to general funding provided by the federal CARES Act. Contact [email protected] for more information or to get involved. By Sarah Schumann When thirty lobstermen linked their fates to establish the Newport Lobster Shack cooperative in 2010, they never imagined all of the ways that this little outbuilding would support their small fishing port. They certainly never could have foreseen that, ten years later, the Shack would keep their fishing businesses afloat during a global pandemic. And yet, that is exactly what it has done.

Once a commercial fishing epicenter on par with the port of New Bedford, Newport’s importance as a fisheries hub has shrunken dramatically in the last half century. Most of the City by the Sea’s wharfage now holds yachts, while a few dozen lobster and gillnet boats defiantly cling to a commercial toehold at Long Wharf (State Pier 9). “We’re surrounded by pretty much the highest end yachts on the East Coast on one side and time shares on all the others,” says David Spencer, manager and member of the Newport Lobster Shack coop. But the Shack, Spencer adds, has become “an anchor that helps to keep the commercial fishing fleet in Newport. It’s really integrated the fishing community into the city, into the state. We’ve become part of the tourist trade here.” Every captain who berths a boat at Long Wharf’s commercial fishing pier is by default a member of the coop and has a vote in any decisions that are made. The lobstermen opened the Shack in 2010, after the Department of Environmental Management put a kibosh on individual off-the-boat lobster and crab sales in Newport. For the first three years, the Shack sold only live lobsters, crabs, and whelk. Then in 2013, the lobstermen added a kitchen, outdoor seating, and a take-out window offering fish and chips, calamari, and an array of crustacean-based fare: lobster bisque, lobster bites, lobster rolls, and fresh steamed lobster. On March 9, 2020, when Rhode Island Governor Gina Raimondo responded to the coronavirus pandemic by declaring a statewide emergency, the coop’s members were busy readying their lobster traps and tuning up their boats for the upcoming fishing season. The Shack had been making an effort to expand shoulder-season business by offering evening take-out meals for Lent, which began on February 26. Now suddenly, all of these plans were up in the air. The coop’s members came together to assess the situation. As David Spencer recalls, “It was apparent that when everybody did start fishing, there would be no place to sell the catch, other than here [at the Shack]. In other words, the restaurants weren’t open. The other seafood buyers weren’t even open. And the price was ridiculously low.” After discussing the possibilities, the lobstermen realized they had only one choice if they wanted to have a fishing season this year: to try to move as many lobsters and crabs as possible through the Shack – even if it meant decreasing the coop’s own profit margins. “As a group,” says Spencer, “we decided to not focus on profits for the coop this year, but to make sure that we could pay the fishermen a very good wage so that they could make it through the season. We felt that was our priority. So we did. We’ve been paying six dollars straight since March, when the price was in the three- or four-dollar range. That’s one of the advantages of having a business model like this. This will not be our most profitable year by any stretch of the imagination, but I think we did the right thing.” By May, some of the other customary buyers were open again, offering the lobstermen additional sales options and taking some pressure off of the Shack to buy the whole catch. As spring turned into summer, the Shack saw some parts of its business do even better than in previous years. The takeout program picked up speed earlier than usual in the season, as homebound families sought to add some excitement to their meal routines. Shipping requests came in from across the country, as people prevented from crossing state lines sought to recreate the flavors of Newport getaways at home. And when the governor gave the green light for outdoor dining in May, the Shack’s long-existing picnic table setup was suddenly en vogue. “We were just fortunate to have the right model to fit into a pandemic, if there is such a thing,” Spencer observes. “What we do seems to fit in with the current circumstances.” This combination of serendipity and a collaborative decision-making model have been a true blessing for the coop’s members, Spencer states. “We certainly recognize that we’ve been extremely lucky this year not to suffer downturns like a lot of other businesses.” That doesn’t mean the coop hasn’t faced challenges. At the height of the summer season, the Shack typically employs 15-20 fulltime and part-time staff to pick lobster meat, prepare ingredients, work the counter, cook customer orders, and tend the live market. But this year, Spencer says, the pandemic “made staffing almost impossible. We lost some really key people last year, and for a little bit, we didn’t feel that we had people who could handle both the fish and the lobster. Staffing has been the biggest problem this year.” The upcoming fall season brings additional uncertainties. In the fall, Spencer explains, “typically our main customer base was cruise ships and bus tours, neither of which will be coming to Newport this year. The boat show draws huge crowds into Newport. That didn’t take place in Bowen’s Wharf. The fall may be a little more challenging. We’ll see.” Whatever the future may bring, it seems likely that the Newport Lobster Shack will continue to be a valuable tool to help its member fishermen remain resilient as circumstances change. “I think that what our main goal should really be is to make this coop and the kitchen and the live market as strong as possible. Look at me; there’s a lot of people my age,” says Spencer, who is 69. “In five years, fishermen at this dock could look significantly different. I think the one thing that can remain a real strong anchor would be the Newport Lobster Shack.” Fishermen and seafood businesses:

Team up with the Fish Forward project to make your vision a reality! About Fish Forward: From now until September 2021, the Commercial Fisheries Center of RI and RI Small Business Development Center are teaming up to support business innovation and resilience in the seafood sector, thanks to general funding provided by the federal CARES Act. Contact [email protected] for more information or to get involved. By Sarah Schumann The façade of Fearless Fish has changed in the last few months. Before the covid-19 pandemic upended business and life across the U.S. in March 2020, customers used to linger in front of a glistening display of perfectly trimmed fish, ogling each item and considering which one to eat for dinner. Now, they line up in the parking lot, behind retractable belts like those found in airport security lines, while the shop’s staff goes inside the shop to retrieve orders that customers have placed by phone or online. Instead of learning about new seafood species by pointing to the bright display and asking, “What is that weird-looking thing?” the shop’s customers now point to a printed list and ask “What is that weird-sounding name?”

It’s not quite the same as it was before. But what hasn’t changed, says owner Stu Meltzer, are the business’ core values. “Our mission is to do our part to help turn this country into a seafood eating nation,” Meltzer declares. “We do that by helping people gain confidence buying fish, cooking fish, eating fish, and trying new types of fish.” Fearless Fish, located on Providence’s West Fountain Street, was only a year old when the pandemic began. Meltzer, a 37-year-old transplant from Chicago, worked for Chicago’s Fortune Fish, Boston’s Pangea Shellfish, and a handful of seafood retail shops across Massachusetts before fulfilling his lifelong ambition to start his own business in February 2019. Providence has been a perfect fit for Meltzer’s style of engaged and interactive fishmongering. He describes his customer mix as intellectually curious. “Part of that is Providence: it’s a very academic town. We get a lot of professors and graduate students. And part of it is just that’s how Providence is. People are intellectually curious. It works, because we’re big on sharing the info on how things are caught and the inside baseball on the fish business.” For example, Fearless Fish sends out a biweekly email blast to its customers. In a recent edition, Meltzer offered an overview of the regional fishery management councils that manage our nation’s federal-waters fisheries—including the controversial subject of why Rhode Island doesn’t have a voting seat on the Mid-Atlantic Fishery Management Council. In another edition, he described how fishmongers calculate the yield of edible product from a whole fish. “Seafood is kind of like wine, where there’s so much you can learn,” Meltzer reflects. “I‘ll be learning stuff forever.” That’s why an important part of Fearless Fish’s approach involves “having a wide variety of different species—some that are better known and more expensive, like a bluefin tuna or a sea urchin—and things that are lesser known that people have less familiarity and comfort with—like cobia, thresher shark, sea robin, skate, or monkfish,” Meltzer adds. “There’s a lot of things that people get worried about or sketched out about with fish. ‘How do I cook this? There’s bones in this whole fish; how do I deal with that? What is sea robin? What is scup?’ Fearless Fish is built around addressing those concerns or issues that people might have.” When the reality of the global pandemic settled over Providence in March, says Meltzer, “Initially it was freaky. Nobody knew what was going on.” Taking their cue from nearby restaurants, he and his staff chose to close Fearless Fish for two weeks. But when the two weeks were over, the staff decided they weren’t comfortable returning to work, so Meltzer and his wife Rose spent another three weeks hiring and training three new employees. When it finally did reopen, the shop only sold frozen fish. This helped customers avoid frequent shopping trips. But by summer, the shop was stocking its usual variety of products. Fearless Fish has also established a presence at several farmers markets across Providence and has reinstated a weekly fish share pickup program that counts 160 residents of Providence, Newport, Cranston, and Warren among its subscribers. If anything, Meltzer says, “Business has been better for us than before. I attribute it to the restaurants being more limited. People can’t go out like they did, so they’re eating at home more. That works for us. Plus, we’re a small shop and with the outdoor pickup, I think people feel it’s safer. Both of those trends have helped us.” Hiro Uchida was one of the customers picking up dinner outside the store on a recent September afternoon. Uchida, who grew up in Japan but now lives in South County, is a self-described seafood thrill-seeker. But before Fearless Fish entered the scene, his Rhode Island seafood experiences left him wanting more. “I wanted fresh seafood,” Uchida explains. “Preferably sushi-grade. I wanted a variety of fish, including unfamiliar and/or local species. I wanted a sense of seasonality -- seafood made available when it is in season. Lastly, I wanted excitement when you find the fish that you were not expecting to find (recent example: cobia). Back home, nearly all fish stores had these. But here, even in Ocean State, I was unable to find one—until Stu's Fearless Fish Market opened. Ever since I first visited Fearless Fish in April 2019, I got hooked. Can't live without it!" When Meltzer thinks about the future of Fearless Fish, he envisions multiple storefronts, an expanded fish share program, and a greater farmers’ market presence. But his most ardent and vexing desire is to assure a constant supply of high-quality local fish for his customers. “I’ve been thinking about ways to do that,” he says. “Some combination of quality incentives and traceability.” If each boat’s catch was tracked with a label as it made its way through the supply chain, discerning local chefs and retail shops like Fearless Fish could select their seafood from the boats producing the highest quality. And fishermen would receive a reward for this quality in the form of a higher price. “I want to crack this,” Meltzer insists. “I want good, consistently reliable product. The customer does too. They’re willing to pay for it. This seems like such a big opportunity for the fishermen do to better, for them to make more [income]. It will take cooperation from everybody: fishermen, dealers, retail. But it’s being done in other places around the world.” Fishermen and seafood businesses:

Team up with the Fish Forward project to make your vision a reality! About Fish Forward: From now until September 2021, the Commercial Fisheries Center of RI and RI Small Business Development Center are teaming up to support business innovation and resilience in the seafood sector, thanks to general funding provided by the federal CARES Act. Contact [email protected] for more information or to get involved. |

October is National Seafood Month, and we want to celebrate our waters’ bounty this year more than ever! Commercial Fisheries Center of RI invites you to follow our blog and social media for a special month of storytelling, as we profile local businesses and the exceptional resilience, grit, and innovative spirit that makes Rhode Island fisheries uniquely resilient.

Blog Topics |

Location |

|